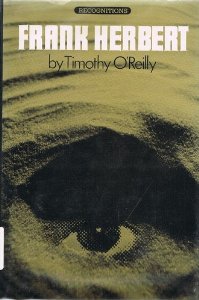

By Timothy O'Reilly

Copyright © 1981 by Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., Inc. (Out of print.)

In the fall of 1977, when I was a couple of years out of college, I received an unexpected call from a friend, Dick Riley. He'd just landed a new job at a small publisher called Frederick Ungar, as the editor of a series of short critical monographs on detective and science-fiction writers. He was looking for authors, and as he knew I was fond of science fiction, he thought of me. Would I write a book about Frank Herbert, he wanted to know.

I struggled with his proposal, but eventually decided to give it a try. It was a momentous decision, since it was in undertaking the book that I came to think of myself as a writer. (Ironically, it was the same day that my programmer friend Peter Brajer asked me to help him rewrite his resume so he could land a job writing a manual--a job that I eventually came to help him with, and which led to our partnership not long afterwards.)

I wrote Frank Herbert over a period of about two years, and it was published in 1981. In the course of writing it, I read all of Herbert's novels, stories, and essays, as well as a lot of his newspaper writing (which, by coincidence, included a stint at the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, the local paper for the region in which I now live.) I interviewed him several times, and, in a small way, we became friends. His ideas came to influence me deeply. I had always loved Dune and Dune Messiah, and especially the idea that predicting the future too closely can lead to a kind of paralysis. But the deeper I went, the more substance I found. Ecology, mysticism, and a kind of hard-headed insistence on the relativity of human perception and the limits of knowledge combine into a richer mix than is found in a lot of science-fiction. There's some really cool stuff here!

My goal in writing the book was not to be a "critic", but an enthusiast. I wanted to share the additional information I'd uncovered, to present it in a way that illuminated Herbert's work without diminishing it or "dullifying" it. In many ways, this was the same goal I embraced as a technical writer, to bring transparent assistance to the reader's own experience, not to replace it with my own.

Like many publishing ventures, Ungar's Recognitions series (as it was called) went largely unrecognized. Ungar itself was eventually sold to another publisher, Crossroads/Continuum, and the book went out of print, where it has remained for many years. (The last time I remember getting a royalty statement was in the late 80's.)

From time to time, I get letters from people asking if the book is still available, and I've always had to tell them no. (I have just two copies left myself--one hardcover, the other paperback--having given away my last "extra" just last year, to none other than Jeff Bezos, when I discovered on our trip to Washington that he was a big Frank Herbert fan!)

Last year, I wrote to Crossroads/Continuum and asked for a reversion of rights to the book so I could put it up on the Web. My letter went unanswered. Since they didn't bother to answer, I decided to go ahead and do it anyway, figuring, as they say, that it's sometimes easier to get forgiveness than permission. If anyone from Crossroads/Continuum notices, please give me a call or drop an email. I'd love to see the book back in print, or if not, at least to have your blessing on this Web version.

I hope those of you who are Frank Herbert fans will enjoy the book, and that those of you who are not (yet) will give his books a try. In addition, a few years later, I put together a book with Frank, a collection of his essays called The Maker of Dune, which was published by Berkely/Putnam. That too is out of print, but since most of the writing in it is Frank Herbert's, not mine, I can't in good conscience pull the same trick of putting it up on the Web. You may be able to find a used copy somewhere, or, if enough people care about it, perhaps the publisher could be persuaded to put it back into print. (Actually, I suppose that I could put up the interviews, which I believe I retained copyright on, but that's a project for another day.)

If you say, "I understand" . . . you have made a value judgement.

--Whipping Star

The highest praise that can be given to an author is to say that his work awakens unexpected possibilities of thought and feeling. I have written about Frank Herbert from this perspective. His work has touched me, and I have learned from him.

To my mind, the most fundamental judgment to be made about a novel is not as a work of art built to abstract standards, but as an act of communication. What does it say to the reader? How does it touch him?

The job of a book like this is not to criticize but to illuminate and intensify an author's statement, chiefly by juxtaposing a wider range of material than would be apparent to a casual reader. The juxtaposition here includes material from all of Herbert's work--his essays, letters, poetry, and short stories, as well as his novels--and from extensive personal interviews with him.

Such an illumination is particularly appropriate with the Dune trilogy, since it is many-layered and its imaginative span is too great to be grasped all at once. The impact of the story is felt, but its meaning is not always understood.

One criticism that I have made of Herbert throughout this book is that he walks a narrow line between entertainment and didacticism. In his best work, such as Dune, the story itself is the message; the concepts are so completely a part of the imaginative world he has created that the issue of didacticism never arises. Ideas are there to be found by the thoughtful reader, but one never stumbles over them. Other works, however, are sometimes unnecessarily obscure. Herbert's shorter novels in particular lack the development of story and character to support the weight of the ideas they contain.

Even so, these shorter novels well repay detailed study. I have found that the more I know about Herbert's work as a whole, the more I am able to enjoy works such as Destination: Void and The Eyes of Heisenberg. Close reading strips away the obscurity, allowing the excitement of what Herbert is trying to say to become the source of the reader's enjoyment.

One word about the mechanics of this book: notes for all references follow the end of the text and are identified by page number and a few words from the relevant passage. No superscript numbers appear in the text. This format is intended to enhance the readability of this study while retaining the full critical apparatus.

A few words of gratitude are also in order. Thanks first of all to Frank Herbert himself, for all the obvious reasons; to Beverly Herbert, for some invaluable perspectives and for the final word on chronology and other factual information; to Ralph Slattery, Jack Vance, and Poul Anderson for sharing their memories; to Albert Lord, for his perspectives on folklore elements in Dune; to Ted Jennings and especially Will McNelly, whose willingness to share their own ideas and unpublished interview material showed me the best traditions of scholarship.

Thanks also to Walt Blum at the San Francisco Examiner, who went out of his way to help me track down articles and friends Herbert had developed there; to Mrs. John W. Campbell for permission to excerpt portions of her husband's letters to Herbert; to Linda Herman of the Special Collections Library at the California State University at Fullerton, for her unfailing help in my, search through the Herbert manuscripts and other papers kept there; to Marty Cohen and Lynne Conlon, each of whom did legwork for me when time kept me from following up important leads; to my business partner, Peter Brajer, for biding his time while I finished this book; and to the MIT Science Fiction Society, whose pooled knowledge and complete collection of science-fiction magazines were so reassuringly close at hand.

Finally, thanks to my wife Chris, for her valuable comments and suggestions, and to Dick Riley, my editor, for his patience, his appreciation, and his thoughtful pruning.

This is the world of Frank Herbert's Dune, considered by many people to be the greatest science-fiction novel ever written, and certainly the pinnacle of Herbert's own art. Each reader finds a different reason for praise. One is struck by the scope of the creation--an entire world, detailed in topography, ecology and culture. Another seizes on the relevance of its ecological themes. All are fascinated by the characters--epic heroes who sweep their worlds and the reader into their struggles. Heroism, romance, philosophy--Dune has all of these, crafted into the vision of a future one might almost believe has already happened, a history stolen from its rightful place millennia hence.

It is said of Paul Atreides, the central figure of Dune and its two sequels, Dune Messiah and Children of Dune: "Do not be deceived by the fact that he was born on Caladan and lived his first fifteen years there. Arrakis, the planet known as Dune, is forever his place." The same must be said of Herbert himself. He has written other successful novels, but all are inevitably judged against Dune. And while his best work can stand alone, several of his shorter novels are so closely intertwined with the evolution of the trilogy that to study them in isolation from it deprives them of their greatest strength.

Herbert's work is informed by an evolving body of concepts to which the Dune trilogy holds the key. By tracing some of these central ideas, their sources, and their development from purpose to final form, it is possible to show how Herbert framed them with stories that insist that the reader use the concepts they contain. Herbert believes that the primary function of fiction is to entertain, but as Ezra Pound, one of his literary models, wrote: "If a book reveals to us something of which we were unconscious, it feeds us with its energy." The best way to entertain is to provoke, to make people think.

Such depth is integral to Dune's enduring success, yet to the reader interested in science fiction only for the marvels of imagination it portrays, the incomparable story of young Paul Atreides and the crusade he sparks, of battles and intrigues with the fate of worlds hanging in the balance, is enough to justify the novel's fame.

Raised on watery Caladan to be a Duke of the Imperium, trained as a "mentat" warmaster with the abilities of a human computer, and carrying the penultimate genes of a secret, centuries-long plan to breed a psychic superman, Paul is orphaned on Arrakis by a cruel twist of Galactic politics. His father is given the planet in fief, then betrayed and deprived of life and power. Paul must flee to a new destiny among the Fremen of the desert. These oppressed people dream of irrigating their planet and transforming its arid ecology. When an overdose of "melange," the spice-drug of Arrakis, triggers in Paul the ability to read the future, he knows how to give the Fremen what they want. Their plan will take hundreds of years, but if they will follow him to victory over the Emperor himself, Paul can promise the transformation in a single generation.

Even in so short a summary, one begins to see Herbert's essential themes. One of his central ideas is that human consciousness exists on--and by virtue of--a dangerous edge of crisis, and that the most essential human strength is the ability to dance on that edge. The more man confronts the dangers of the unknown, the more conscious he becomes. All of Herbert's books portray and test the human ability to consciously adapt. He sets his characters in the most stressful situations imaginable: a cramped submarine in Under Pressure, his first novel; the desert wastes of Dune; and in Destination: Void the artificial tension of a spaceship designed to fail so that the crew will be forced to develop new abilities. There is no test so powerfully able to bring out latent adaptability as one in which the stakes are survival.

In Dune, each of the players--the Emperor, the Baron Harkonnen (archenemy of the Atreides), the monopolistic Spacing Guild, even the seemingly wise Bene Gesserit gene manipulators--tries either to dominate the situation or to control it in such a way as to minimize his own risks. And in the end all are overwhelmed. The elemental forces of history can only be ridden, not controlled. Paul alone is victorious, because he chooses to ride the whirlwind. He risks everything. His initiation by the Fremen into riding the sandworms is symbolic of his choice. These predators represent all the elemental forces of Arrakis: their native name means "maker," and they are the heart of the ecological matrix of the planet, source of the spice, the sand, and thief of water. And, like nature itself, they abhor artificial boundaries; they are drawn irresistibly to destroy the protective energy shields relied on by off-worlders. They close the desert to all who try to isolate themselves from it; only the Fremen "sandriders," who move with the rhythms of the desert, and mount the fearsome worm, can brave its wilds.

The opposition between isolation (or control) and adaptation to an environment is also shown in the ecological transformation described in the novel. The first stage of the transformation is mastery of the shifting sand dunes. Herbert had noted in the research on dune control, which first led him to the idea for the story, that dunes are very like slow-motion waves. Only those who can see them as waves can begin to learn how to deal with them. In addition, the spice wealth of the planet is a by-product of the life cycle of the sandworms, creatures of the deep desert impossible to raise in captivity; so any plan to change the human environment must preserve a large measure of the worms' original habitat. Men must learn to live with the desert. They can never hope to tame it completely.

It is a general principle of ecology that an ecosystem is stable not because it is secure and protected, but because it contains such diversity that some of its many types of organisms are bound to survive despite drastic changes in the environment or other adverse conditions. Herbert adds, however, that the effort of civilization to create and maintain security for its individual members, "necessarily creates the conditions of crisis because it fails to deal with change." Paul's enemies are hopelessly out of step because they have forsaken their adaptability for the attempt at control. Assurances of survival such as power, traditions, beliefs, and causes have become more important to them than the actuality of survival. Their substitutes for adaptability can sustain them only in the limited enclaves of civilization, not in the wide open spaces of the desert, or in the terrifying futures Paul opens himself to in his visions.

Paul's opponents try to tailor a surprise-free future for themselves, but in a subtler, far more insidious way, the fear of the unknown also corrupts Paul's followers. The drama of the book, and especially of its two sequels, Dune Messiah and Children of Dune, builds around the tension between Paul's very real prophetic powers and the results when he puts them to use in the attempt to regain his throne. To achieve his powers was a triumph of self-mastery and confrontation with the unknown, but to exercise them inevitably means to limit those qualities in others. Though Paul exhorts his followers to imitate his self- reliance, the very state of mind by which they are drawn to him necessitates its opposite. The Fremen seize on Paul as a prophet because he has confronted the uncertainty of the universe and brought forth reassurance for those who cannot or will not find it for themselves. Their deep longing for a messiah is a sub- mergence in a group hunger for an overriding purpose; it is an escape from the individual greatness Paul himself displays.

In Herbert's analysis, the messianic hunger is an example of a pervasive human need for security and stability in a universe that continually calls on people to improvise and adapt to new situations. In the backwaters of history, or its Golden Ages, civilization plays the part of a parent, providing not only warmth and security and meaning, but a limited arena within which an individual can exercise his powers with some hope of actually dominating the situation. A conspiracy of family, culture, and religion manages to convince the individual that he is not alone, that he does not need to struggle, but only to take up his birthright. In times of crisis, or on the fringes of hardship and oppression, men become all too aware of the uncontrollability of the universe. They long for messiahs and saviors, dreaming that such men have the certainty they lack.

Like most science fiction, Dune is built on the question "what if... ?" What if there really were a man, godlike in knowledge and wisdom, who could grasp that ungraspable universe and bring it to heel? The Dune trilogy is Herbert's answer to that question. He says:

I had this theory that superheroes were disastrous for humans, that even if you postulated an infallible hero, the things this hero set in motion fell eventually into the hands of fallible mortals. What better way to destroy a civilization, society or a race than to set people into the wild oscillations which follow their turning over their judgment and decision-making faculties to a superhero?

In the end, such a savior would avail mankind nothing. It is our own awakening we must seek. So when we are stirred by Paul's courage and genius (and this, cunningly portrayed, is really the heart of the book), we must use him as an inspiration, not a messiah. We can find those same qualities of heightened consciousness in ourselves.

One of Herbert's working assumptions as a writer is that he can speak directly to parts of the reader's consciousness that the reader himself may not be aware of, and thereby create unexpected effects. For instance, he says, "In some people, simply confronting the idea of hyperconsciousness sharpens their mental alertness to a remarkable degree." He has noted that this is a common reaction, and on this he has banked--with great success--in Dune. Reading the story of a man before whom space-time barriers fall, and who can read human motivation as though it were shouted aloud, we are nudged by the possibility of being the answer to our own dreams.

The human potential for hyperconsciousness is central to such science fiction classics as Clarke's Childhood's End, Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land, and Sturgeon's More Than Human; even Asimov's Foundation trilogy touches on the idea. The treatment of hyperconsciousness in such works can include heightened perception of environment, self and others, and a consequent sense of power and transcendence of the limits that usually confront human beings, as well as a kind of moral evolution. Those who possess such consciousness are considered to be somehow fundamentally better than those who do not. But while Herbert places great value on higher consciousness, he does not see such a state as "the" answer to mankind's problems. He is extremely suspicious of utopian fantasies, whether embodied in a social order or in a state of consciousness. In an infinite universe, where anything can happen, more consciousness simply means new kinds of problems. "The reward of investigating such a universe in fiction or in fact," he says, "is not so much reducing the unknown but increasing it, opening the way to new dangers, new crises." The most important consequence of Paul's ability to see the future is not that he can control what happens but that he can respond more ably. Although his power over the course of events is greatly amplified, so too is his awareness of the forces with which he is grappling. Paul is like the mythical giant Briareus, who had one hundred hands, but also fifty bellies; he had as much trouble procuring food for himself as the next man. Paul has no more real control over the universe than anyone else, and at times less.

All of these ideas reflect the ecologist's emphasis on variety and adaptability as the key to the stability of ecosystems. However, Herbert has not been influenced by ecology alone in formulating these ideas. He is responding to the profound changes of the past seventy-five years in the philosophy of science. Around the turn of the century, famous scientists expressed their sadness that the great adventure of science was nearly at an end: nothing really significant remained to be discovered. Optimism ran high that man was on the threshold of immediate and total technological domination of his environment. But dreams of unlimited development have led to discoveries and devices that inescapably undermine those dreams. Everywhere the scientist of today looks, he perceives mystery. Einstein's theory of relativity postulates that there is no absolute reference point for our observations. Heisenberg's "Uncertainty Principle" demonstrates that the very act of observation skews the result of certain experiments. G del's theorem proves that all mathematical systems rest on propositions that are unprovable within the system, and conversely, that there are an infinite number of true propositions within any consistent mathematical system that can nonetheless never be deduced from it.

It usually takes about fifty years for the discoveries of science to penetrate popular consciousness. Einstein's special theory of relativity was published in 1905, the general theory in 1916, Heisenberg's principle and G del's theorem in the 1930s. These ideas were soon picked up by science-fiction writers, but their treatment consisted primarily of fanciful applications of these ideas and inventions based on them. Only recently have writers begun to consider the implications for our picture of the universe and how it functions.

The entirety of Herbert's work is an attempt to remake that picture. His use of the ideas of physics is not practical and predictive, but almost completely metaphorical. The relativity he is interested in is the relativity of our perceptions and our cultural values. In a universe that is "always one step beyond logic" (as Paul describes it in Dune) it becomes essential to look at the nature of our logic, and the role of our preconceptions in shaping what we see.

Herbert uses the term "consensus reality" to denote the body of common sense that constitutes the editorial board for perception in any culture and time period. Right now we are at a point of turnover, when one long-standing consensus reality is giving way to another. To Herbert the implicit lessons of our whole culture bid us to cling to old ideas even when we have intellectually embraced the new. We are still looking for absolutes in a relativistic universe, for stability in a sea of motion. We are looking for causes and effects when our new knowledge tells us we should be looking for contexts and matrices. We are looking for the conscious foundations of individuality when we should be looking at the biological base of our species and asking what beyond that is individual. Our common sense has gone sour, our foundations have become boundaries. The problem is that we are growing too fast; we don't have time to make a graceful changeover. It is no longer possible to operate on the basis of old data without coming to grief. We need to start working from new data as soon as it becomes available. How can we deal with the time lag?

Herbert's science fiction offers part of the answer. Science fiction is not a predictive but an informative tool, which seeks to prevent mistakes by trying to keep up with change rather than to stop it. Herbert says: "if I'd been born in my grandfather's time, I'd have made my grandfather's mistakes. There's no doubt of it. I just don't want to make my grandfather's mistakes today." As a result, his novels not only teach new ideas, they comprise implicit lessons to counteract those from his readers' early training.

To explore the power struggles of a galactic empire or the ecological salvation of an imaginary planet might seem to have little bearing on the world we know, but when such stories are spun from Herbert's mind, they profoundly illuminate the here and now. Author and critic Samuel R. Delany has written, "Science fiction is the only area of literature outside poetry that is symbolistic in its basic conception. Its stated aim is to represent the world without reproducing it." Herbert himself notes that science fiction allows him to "create marvelous analogues." He says:

If you want to get anything across, you have to be entertaining first. If you start standing on a street corner, people will tune you out. We human beings tend to have very good filter systems in our heads to see and hear only what we want to see. But analogues give you a marvelous device for getting past that screening system, because people can be caught up in the drama of the story, be deep into the problems of it. Then later on, much later on, they say, Oh, my God, he was talking about this!" And they come out of it with a brand new view of what's happening in their world.

Herbert's work shows the possibilities for good and evil of factors present, but unnoticed, in our culture. He gives his readers ideals and dreams, but not as an excuse for avoiding the realities of the present. He wakes us up to the dark side of our dreams, and thereby gives us somewhat more of a chance to redeem that dark side. Most of all, he offers a chance to practice in fiction the lessons that are increasingly demanded by our lives: how to live with the pressure of changing times, how to flow with them rather than resist them, how to seek out really new possibilities in a world in which every path seems increasingly predetermined.

Herbert's analogues are strongest when they are least obvious and can do their work on an unconscious level. The cultural patterns modeled by the Dune trilogy, for example, are not simply reproduced but are, as Delany notes, represented in a fable with an inner life all its own. Many of the features of the superhero mystique that Dune sought to unveil were not made explicit until the third book of the trilogy, fourteen years later. The "pot of message" Herbert offers is worked into the design of the entire tapestry; the analogue is not enfeebled by premature expression. The reader is told a story. He must draw his own conclusions.

Herbert has developed fictional techniques which demand that the reader sharpen his perceptions and powers of judgment. He says:

We come from a spectator society, by and large. Whatever entertainment you produce is supposedly for passive receptors, who sit there and take it.... There are a lot of conventions, and you're supposed to gratify all of them. My contention is that entertainment has a far greater arena in which to perform. But to perform in that arena you make demands on your readers.

One such demand--providing an opportunity for his readers to engage their consciousness--is the building up of images from the unusual cues Herbert supplies. In the Dune trilogy certain kinds of scenes--confrontations, love, tragedy--are invariably accompanied by the same background images, colors, or smells. For instance, whenever dangerous confrontations occur, the color yellow is present. Herbert says, "By the time you're well into the book, if you tell them that there was a yellow overcast to the sky, they're sitting there waiting for something bad to happen. 'There is also consistent attention to who sees things. Point of view is always deliberate. "I treat the reader's eye as a camera," Herbert says. There may be a generalized view of a scene, which is followed more and more by a concentration on the area in which the action is going to happen. Finally the eye is brought in for close-ups, "a hand tapping on the table, or somebody's mouth chewing the food."

In using such techniques, Herbert feels he is talking subliminally to the reader. The tremendous illusion of reality the novel conveys is the result of years of thought, layered so that only the most important details catch the eye, and others speak directly to the unconscious. At the same time, however, much that is ordinarily perceived subliminally is made conscious: the expression of emotion in nonverbal gesture, colors, smells, sounds are all noted and evaluated by the characters. Because details that took the author hours to assemble are absorbed by the reader in minutes, the fiction of hyperconsciousness takes on a kind of reality.

The greatest demand that Herbert makes upon his readers is not on perception, however, but on judgment. Most science-fiction novels (except those that are overtly dystopian) are variations on the heroic success story. In the Dune trilogy, Herbert portrays a hero as convincing, noble, and inspiring as any real or mythic hero of the past. But as the trilogy progresses, he shows the consequences of heroic leadership, for Paul, his followers, and the planet. Anyone devoted to the heroic ideal stands to be devastated by the conclusions of the trilogy. Herbert demands that his readers look at their expectations, their heroes, and exactly what they mean by success.

The structure of Herbert's novels reinforces this process. His plots tend to be extraordinarily complex. One level of action after another is introduced, any one of which seems enough to carry the story. Not until late in the novel is the tapestry being woven by these threads revealed. Even then Herbert does not employ a hierarchical organization, in which fact upon fact lead to some ultimate understanding, which is, in effect, the final reduction. The achievement of the meaning, the theme, the answer, while it appears to be an achievement of the broadest truth, is actually accomplished by the elimination of all the possibilities inherent in the original situation. Herbert doesn't write the traditional kind of story in which a hero overcomes the obstacles between here and happily everafter.

Herbert's unwillingness to let himself be trapped into a final position gives his books an often frustrating ambiguity. It is just at this point that the books demand, if the reader is truly to understand them, that he begin to respond on unaccustomed levels. He must let go the need for certainty and absolute points of view. Herbert's novels demonstrate the action of principles as much as of character, and show the many sides of each situation with equal sympathy. One could say they are training manuals for exactly the kinds of awareness they describe.

Certain experiences, though, were sufficiently powerful to stand alone. They determined the shape of Herbert's life and thought. The most important fact of Herbert's literary biography is his career as a newspaper reporter. He worked for many small West Coast papers and then, in 1959, settled at the San Francisco Examiner for over ten more years, as a writer and editor for the newspaper's California Living magazine. He took a brief leave of absence after completing Dune, devoting himself full time to fiction, but soon returned to newspaper work. He did not become successful enough as a science-fiction writer to stop working as a reporter and editor until 1969. At that time, he moved back to Washington, his home state. Even then, he kept open some links to journalism. He worked for a short time at The Seattle Post-Intelligencer to help its new editor, a former colleague from the Examiner, get started, and occasionally did special articles for the paper thereafter.

Herbert's work in journalism is important because it set the methodical style of his research. It is no accident that two of his novels, Under Pressure and Dune, began as newspaper magazine feature stories. Herbert is famed among science-fiction writers for the depth of fact with which he shapes his books. It is not the richness of a single science explored in detail, as in the work of Hal Clement, but of a wide-ranging mind that can put Mohammed, ecology, and Jung together in one consistent and entertaining fictional world. Herbert gathers facts, then looses them all into his imagination to be reshaped into fiction. He calls this process "loading the computer."

Herbert has loaded his computer with life experience as well as concepts. For a writer as obsessed with ideas as he is, Herbert is remarkably insistent on the concrete. "The verisimilitude of the surround is half the battle," he says of the effort to get his ideas across. "And believe me I'm a reporter.... [For instance,] when I talk of a Senate hearing, I was there, I know what they're like, I know how people speak in them. So my characters react the way real people have reacted under similar circumstances."

However, Herbert's pursuit of verisimilitude is extreme even for a reporter. He does not like to write about anything that he has not experienced firsthand, at least in microcosm. For instance, when the Examiner asked him to be its wine writer, he refused until he found someone to train him in wine-making as well as imbibing. The number of his secondary "careers" attests to his desire to back up thought with personal experience: photographer, television cameraman, oyster diver, lay analyst. He was a campaign worker for Washington State politicians and a speechwriter in Washington, D.C.; his concern with politics and bureaucracy is founded in part on such experience. At one point, while in Washington in 1954, he applied for a job as governor of American Samoa, and came, he believes, very close to getting the post. He was betrayed by his own ingenuous hunger for experience, which the government found lacking in career- mindedness.

The world model that may be drawn from Herbert's fiction might be of a reporter's society, in which the ability to confront the everyday with questions that penetrate its ordinariness belongs to everyone. Science-fiction writers and newspapermen are motivated by the same insight: "There's a story in this." Herbert described a great deal about his fictional approach when he said, "I'm a muckraker, a yellow journalist," and elsewhere, "I ask myself, 'What is the society avoiding?'" Like a science-fiction plot, news--especially feature news of the kind Herbert liked to write--may be in sight for years, but so obvious it is ignored.

Herbert's study in the Dune trilogy of the superhero mystique is a good example of this journalistic technique. He has said that the function of science fiction is not always to predict the future but sometimes to prevent it. His comment on the work of Huxley and Orwell can equally well be applied to his own: "Neither Brave New World nor 1984 will prevent our becoming a planet under Big Brother's thumb, but they make it a bit less likely. We've been sensitized to the possibility."

Herbert's concern with raising consciousness by means of his stories is of course more than just future-oriented investigative reporting. As has already been suggested, the consciousness he is trying to awaken has psychological as well as social dimensions. In addition, he is insistent in developing ideas that have the power to awaken his readers, because he considers that to be the best kind of storytelling. Even at his most pedagogical, Herbert is not primarily seeking to convince, but to entertain.

Herbert has always seen himself as a storyteller, and only secondarily as a writer of fact. He remembers coming down to breakfast on his eighth birthday, the one day a year when "everything on the table was laid to my precise demands," and announcing that he was going to be "a author." That was it, he insists. He never changed his mind. "I thought that I was good at telling stories, that I could entertain," he recalls. "And I did, from a very early age."

Another major influence on Herbert's thought was his country upbringing. He was born in Tacoma, Washington, on October 8, 1920, and spent most of his youth on the Olympic and Kitsap peninsulas of northwest Washington. His father, Frank, Sr., ran a bus line between Tacoma and Aberdeen, and later became a member of the newly formed state highway patrol. Although the family did not operate a farm, they always lived in areas "sufficiently lightly populated that you could keep your own chickens and a cow."

Herbert feels that the country left him with a self-starter mentality, one not dependent on outside help. He argues that "in the city, if your [car] breaks down, you go to the garage and if it's closed you throw up your hands and say you'll come back Monday. In the country, if your hay-baler breaks down, you've got to get the hay in, and you say, 'Well, get me the tool kit!'"

This experimental, problem-solving approach to technology finds high praise in several of Herbert's novels, as well as in his choice of life style since his retirement from journalism. He now lives on a small farm in Port Townsend, Washington, which he calls an "ecological demonstration project," an example of new-style "techno-peasantry. His ecological homestead includes a heated swimming pool and sauna as well as the obligatory greenhouse for vegetables and supplemental solar heating, and he plans to build a small gymnasium to accompany the chicken coop. He has built a pond for ducks as well as for climate regulation on his land; his chickens provide not only food but manure for fertilizer and for the production of methane gas. He is involved in home computers and windmill design. His purpose is to show that, by developing alternative energy sources and by taking individual responsibility for the way we live, we can maintain a high standard of living without cutting ourselves off from the natural world. Though much of his writing explores the potentials for disaster in contemporary behavior, he has great faith in the power of individual creativity. He says:

I think the sky is going to fall. I predict blackouts, more strikes, starvation, all kinds of urban violence. But on a positive note, I also think we are still a society of screwdriver mechanics. Our society is particularly rich in people who, faced with a problem, don't sit down and say, "We are doomed"; but instead ask, "How are we going to solve that?"

Improvisation has become something of a principle for Herbert. He says.," One of the most beautiful things that we have going for us is surprise." His heaven is a universe of surprises that we must meet with only our ingenuity as a tool. His greatest fear is that we will

[tie] ourselves into situations where we can't change our minds.... I think it's a mistake to think about THE future, one future. We ought to think more of planning for futures as an art form, for quality of life. We have as many futures as we can invent.

Herbert was originally drawn to science fiction because it favors this kind of improvisation, at least in thought. He feels that "science fiction is to mainstream fiction as jazz is to classical music. It is no accident that he also refers to conversation, the province of the oral entertainer, as a "jazz performance."

Herbert attributes his rural upbringing with having instilled in him a "landmark consciousness" rather than a "label consciousness," a predisposition that found fruit in his later interest in general semantics. Country pragmatism doubtless contributed as well to his choice of journalism as the compromise career for a fledgling storyteller. "You do things which are necessary," he says. It's very romantic to think about taking your family to the garret with you, but it doesn't work out very well in a practical sense. ' The actual impetus to journalism was more direct, however. A local reporter ran Herbert's high school newspaper like the real thing. "There wasn't one of us who couldn't have worked as a reporter after that," Herbert remembers. "And many of us did." While still a teenager, he began to work as a summer stand-in for vacationing reporters.

About 1939, Herbert moved to southern California with a high-school friend. He obtained a job with the Glendale Star after lying about his age and spent his free time across the border in Mexico. He was married in 1940 and had a daughter, Penny. He joined the U.S. Navy soon after the war began and was divorced before it ended. After his tour in the Navy ended in 1944, Herbert moved back to the Northwest, working brief1y for the Oregon Statesman in Salem and the Oregon Journal in Portland. During this period, he wrote a number of short stories that were published in slick magazines under a pseudonym he refuses to reveal. "I'm not very proud of them," he says. "They were mostly hack work."

Also in 1944, Herbert heard that Lurton Blassingame, a literary agent in New York, was looking for new writers. Blassingame accepted Herbert's work, and they began an association that has lasted until the present. Herbert feels that Blassingame has acted not just as his agent, but has performed the most crucial function of an editor as well--helping him to achieve an objective distance from his own work.

Herbert published the first story under his own name in the March 1945 issue of Esquire. "The Survival of the Cunning" is a war story that takes place in the arctic, and which turns on the superior adaptation of the Eskimo to his environment. Scouting for Japanese radar posts, an American and his Eskimo guide come upon their goal, only to find it empty. They are surprised inside by a returning Japanese soldier. In the warmth of the radar hut, the enemy covers them with a submachine gun, and then takes them outside to finish them. But it is he who is finished instead, because the Eskimo knows that the gun, which was warmed up inside, will freeze and stick once they go out. He kills their captor with a knife. The Eskimo does not know what this crazy war is all about, but he does know how to survive.

In 1945, Herbert moved to the Post-Intelligencer in Seattle so that he could go to school at the University of Washington. He stayed only one year. "I wasn't interested in a degree," he says. "I was always interested in writing. I looked on schools, especially the higher levels, as a kind of cafeteria line." Education, like journalism, was a tool, not an end in itself. Fiction was Herbert's dream all along.

Herbert met Beverly Stuart in a short story class at the University of Washington. They were married in June 1946 and have two sons, Brian, born in 1947, and Bruce, born in 1951. Herbert says of Beverly, "We recognized early on that a marriage was an entity, a third person in a sense, and we put everything into it.... She's the best thing that ever happened to me." Beverly supported Herbert's drive to be a writer, even in a field with as little financial promise as science fiction. Frank periodically took time off from newspaper work, cared for the children and the house, and devoted himself to storytelling while Beverly continued to work as an advertising copywriter.

After leaving school, Herbert went to work for the Seattle Star. The paper folded, and he went to the Tacoma Times, which suffered the same fate. Fortunately, a former staffer from the Tacoma paper who had recently gone to Santa Rosa, California, telephoned Herbert to join him at the Press-Democrat. This move, in April 1949, was to prove significant, for it was in Santa Rosa that Herbert met Ralph and Irene Slattery, two psychologists who gave a crucial boost to his thinking. Any discussion of the sources of Herbert's work circles inevitably back to their names as to no others. They are the one exception to the principle that books loom larger than people as influences on his self-educated mind. Perhaps it was because they guided his reading into new avenues as well as sparked thoughtful conversation. "Those wonderful people really opened a university for me," he says. Ralph had doctorates in philosophy and psychology. Irene had been a student of Jung in Zurich. And both of them were analysts... . They really educated me in that field."

Herbert met the Slatterys by chance, when he and Beverly sat next to Ralph in the audience of a talk Irene was giving at a local church. They became good friends. Herbert recalls Ralph and Irene as teachers, but Ralph demurs. "It was a relationship of common interest and understanding of each others' points of view," he says. Nonetheless, Herbert's work thereafter bears the stamp of his association with them.

Ralph Slattery was an eclectic psychologist. Although originally trained as a Freudian, he based his work chiefly on his ability to make contact with the patient's inner world. In his work as a staff psychologist for the Sonoma State Hospital and as a court examiner in hundreds of adult and juvenile cases, he relied chiefly on in-depth interviews with the people concerned--a method that could not help but appeal to the reporter in Herbert. "I don't think you can approach and understand a person merely from the standpoint of theories," Slattery says. And furthermore:

If you want a real understanding of the human mind, why, you not only have to have the idea or the intelligence or something that can be expressed in terms of the rational or intellectual, but you also have to have the feeling that goes with it... . These are the views we [Slattery and Herbert] shared."

Because of his background in philosophy Slattery also tried to relate psychological issues to broader questions of human nature and destiny. He was critical of the pretensions of psychology to have all the answers to such large questions as were raised by philosophy, and the names of Heidegger, Jaspers, and other philosophers were as likely to be invoked in his conversation as the names of Freud or Jung. The Slatterys also introduced Herbert to Zen, the teachings of which have had a profound and continuing influence on his work.

Irene Slattery worked in private practice as a Jungian analyst. Where her husband gave Herbert a broad theoretical overview, Irene heightened his psychological perceptiveness. One interest she shared with Herbert was in the budding science of nonverbal communication, the hidden messages of the body that complement--or contradict--the spoken word. Inspired use of nonverbal perception, both as a subject and as a descriptive technique, marks Herbert's work. Toward the end of his association with the Slatterys, Frank even briefly set up a private practice as a "lay analyst." The exploratory psychologies in his novels illustrate why he did not maintain an analytic practice for long. However, both Jungian and Freudian concepts remain as an underpinning in his novels.

It was at this time also that Herbert wrote his first science-fiction story. "I saw clearly," he recalls, "that science fiction was going to be the thing." Further:

My feeling about it was that here was an entire field that could be mined for drama, where there was no limit to the settings that could be created. And I like the idea of being in an open ended system. I leaped into it. It was made to order for my purposes.

That first science-fiction story, "Looking for Something," was published in the April 1952 issue of Startling Stories. It concerns the queer belief of a stage hypnotist that the world he and everyone else sees is the illusion of a master hypnotist. And of course it is. An ancient race of alien beings hidden from sight by hypnotic command farms humans for a glandular secretion that provides them with a kind of vampiric immortality. Paul Marcus, the hypnotist, is discovered by the chief indoctrinator of the aliens just as he is on the point of unearthing the master hypnotic command buried in the mind of his pretty young assistant. He is not killed; he is simply reprogrammed to another fantasy life, as a street-car driver instead of a hypnotist. There he will have no need for unsettling thought, the indoctrinator concludes before going off to handle his next case.

"Looking for Something" is a rather naive and obvious story in many ways, but that was often the style of science fiction at the time. Writers had the air of little boys who decided nothing was forbidden and proceeded to look around for cookie jars to open. Many stories were based on the kind of twist Herbert uses here--a tongue-in-cheek attempt to turn the world upside down, to argue that things aren't quite what they seem. The story also touches on such stock sci-fi speculations as the destruction of Earth's sister planet to form the asteroid belt (too many of its inhabitants had "woken up"). It is worthwhile to note, however, that the story reflects many of the same psychological and social concerns that have occupied Herbert ever since. The theme of hidden conditioning, for instance, recurs throughout his work with increasing power and subtlety. What is sketched in this story in the half-humorous guise of hypnosis is later detailed as a full range of linguistic, social, and psychological patterning. The story also takes a satirical slap at bureaucracy--another theme that has continued to concern Herbert. Mirsar Wees, the alien indoctrinator, must report the problem that has occurred in such a way that he absolves himself of all guilt and insures his tenure:

Bureaucracy has a kind of timeless, raceless mold which makes its communiques recognizable as to type by the members of any bureau anywhere. The multiple copies, the precise wording to cover devious intent, the absolute protocol of address--all are of a pattern, whether the communication is to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation or the Denebian Bureau of Indoctrination.

Mirsar Wees knew the pattern as another instinct.

Like many of his key concepts, Herbert's concern with the failings of bureaucracy cannot be traced to any one source. Herbert does recall that when his father was a highway patrolman, the police force had not yet become a legalistic bureaucracy. "The old time cop was judge and jury and everything else.... The whole thrust [of the old system] was not to cause any waves, to get on with the business of living." Faced with a drunk driver, for instance, the elder Herbert would "drive him home and tell his wife to hide the keys till he'd sobered up."

Herbert's eyes may have been opened up to the new wave of the future when he came out of the Northwest. While in the Navy, he was struck by the institutionalized mediocrity represented by the Bluejacket's Manual (he satirized many of its tenets in his 1966 story, "By the Book"). However, the sense of bureaucracy as "instinct" is original vintage Herbert, anticipating his later treatment of bureaucracies as self-perpetuating species with an ecology all their own.

In addition, Herbert admits to having been stylistically influenced by Ezra Pound's poetry, which gave him "a sense of the possibilities of language," so it is not impossible that he was touched also by Pound's prose works such as "Bureaucracy the Flail of Jehovah."

Herbert's next published science-fiction story is altogether more accomplished. "Operation Syndrome," published in the June 1954 Astounding, follows a similar pattern to the previous story--boy meets girl, and with her begins an attempt to crack the artificial walls of limited awareness--but the pacing is much tighter, and the story full of intriguing background. Herbert has abandoned whimsy for adventure. The characters are interesting in themselves, not just cardboard vehicles for a totally conceptual twist of plot.

A plague from nowhere has rocked the world. In each of nine cities, everyone has suddenly, completely, shockingly, gone mad. Dr. Eric Ladde, and every other psychiatrist, is trying to fight the plague. His approach, scoffed at by his colleagues, is to complete the "Amanti teleprobe," an electronic mind reader. Then one night, perhaps fevered by overwork, he begins to dream of a beautiful singing woman. He has never seen her before. He is shaken by the intensity of the dream, but otherwise everything is normal--until he meets her on the street. Swiftly he is drawn into a bizarre chain of events, which reveals to him the true cause of the so-called "scramble syndrome."

The woman, Colleen, and her accompanist, Pete Serantis, are the musical sensation of the decade--and they have played in every city where the syndrome has struck. Ladde discovers that in each case the plague has appeared just twenty-eight hours after they have left. The "musikron" played by Pete Serantis can only be a telepathic instrument similar to the one he himself is working on. It wreaks disaster rather than healing, because it opens people to the collective unconscious without availing them of the safeguards of training or even expectation. When the machine is turned off, they are left without anchor in the strange underworld of the mind.

To further complicate the situation, Pete is using the instrument to dominate people rather than to understand them--or himself. The machine picks up his brainwaves and imposes them on others as a kind of "scrambling impulse" below the threshold of consciousness. Ladde tries to explain the problem to the musicians but Pete is crazed by jealousy (since Colleen and Eric have fallen in love) and refuses to heed. It is a trick to take Colleen away from him, he says. Colleen believes Pete, not Eric, and leaves with him for their next engagement.

The remainder of the story details the psychiatrist's race against time to complete his own telepathic instrument before disaster strikes a tenth city. He succeeds, but too late for Seattle. Now begins the long task of reconstruction. He realizes that "the patterns of insanity broadcast by Pete Serantis could be counterbalanced only by a rebroadcast of calmness and sanity." But he must first find that sanity in himself. He was himself saved from madness only by the rudimentary acclimatization to the teleprobe given him by his research. Ladde is no more at home in the subconscious than others are; he has just built up a resistance to being "scrambled." The completed teleprobe opens Ladde to the unintegrated levels of his own psyche, where he confronts himself in a kind of ultimate psychoanalysis. Once this is accomplished, the device gives him undreamed of capabilities. Starting with his own analyst, he is able to draw other psychiatrists into a telepathic network that can begin to restore the afflicted millions, as well as, presumably, develop new heights of human potential. Having seen that Eric was in the right, Colleen returns. The story ends as the lovers are reunited, to the knowing chuckles of "the network."

Although Herbert employs esoteric electronic gimmickry and extrapolation from electroencephalography to suggest the birth of a new science, the real key to the story is the process of self-discovery Eric has to go through before he can find safety in the new realms of the mind. The machine alone can do nothing. Pete had the teleprobe but worked only harm. "A person has to want to see inside himself," Ladde realizes, "or he never will, even if he has the opportunity." One must go through the process of self-discovery alone. To become a psychoanalyst, Ladde himself had to be analyzed, but his final analysis must be self-analysis. In the process he sees that his formal psychoanalysis was itself part of a continuing neurotic search for a father substitute.

Herbert clearly has a great deal of respect for analysis, but he was not above poking fun at the authoritarian posturing of individual psychiatrists. The story begins with a touch of satire, when Ladde first has his feverish dream of Colleen and the musikron: "A psychoanalyst might have enjoyed the dream as a clinical study. This psychoanalyst was not studying the dream; he was having it." Psychiatry is successful in the end, but only after being purged by its own failure and submitting to an entirely new approach.

After "Operation Syndrome," stories flowed more quickly. "The Gone Dogs," published in the November 1954 Amazing Stories, concerns the fate of the last dogs on earth--struck by a deadly virus, they had to become different to survive. "Packrat Planet" (December, 1954), based on Herbert's experience at the Library of Congress as a speechwriter and research assistant for Oregon Senator Guy Cordon in 1954, explores the value--and the power--of freedom of information, however "useless" it might appear. "Rat Race" (July, 1955) again involves the concept of alien intervention in human affairs--this time we are experimental animals--and recounts the adventure of the man who had the courage to try to step out of the laboratory. "Occupation Force" (August, 1955), a story of alien invasion, suggests quite the opposite, that we are the aliens. The invaders land, looking surprisingly human, and when asked if they intend to occupy the planet, reply, "It should be obvious to you that we have already occupied Earth . . . about seven thousand years ago. Each of these stories reveals Herbert's cachet for reversing, in the course of the story, assumptions that were taken for granted at the start.

With the publication of his first novel, Under Pressure (also titled Dragon in the Sea), Herbert was recognized as a major new science-fiction talent. The book, which was first published in three installments in Astounding, beginning with the November 1955 issue, was an immediate hit.

Under Pressure takes place sometime early in the twenty-first century. The United States has been at war with the "Eastern Powers" for sixteen years. The overall dimensions of the conflict are never detailed, but we learn that the British Isles have been completely devastated by atomic attack, and we may presume that Europe has been swallowed up. The war seems to have settled into an angry stalemate, with each side struggling for minute advantages. After years of this sort of contest, supplies of oil have grown short, and the Navy has begun to pirate oil from undersea fields deep in enemy territory. It is up to the men of the sub- marine corps to steal that oil, using huge inflatable plastic barges drawn by tiny four-man subtugs. For two years the audacious program has worked.

Suddenly, however, something has gone wrong: of the last twenty missions, all have been found and destroyed by the enemy. It is suspected that the "Eastern Powers" are being led to the subtugs by tight-beam broadcasters hidden on board and triggered by "sleeper" agents planted long before the war. And in addition to the enemy successes, the stress of the undersea war is driving submariners insane. Morale is dropping, and success on the next mission is essential. The Navy has chosen the crew with the highest-rated chance of success, barring one problem--the sub's electronics officer became psychotic at the end of its last voyage. To replace him, Ensign John Ramsey, an electronics expert who is also a psychologist, is assigned to the sub. He has a dual role that is hidden from the crew: not only must he perform every function of the expert submariner whose place he is taking, he must uncover the sleeper agent and see that the men make it through the mission without cracking up.

Ramsey and the crew of the subtug Fenian Ram are launched into an undersea world of danger, intrigue, and unbearable psychological pressures. The four men face not only the accustomed dangers of war in the deep--locked in a fragile, closed environment where the slightest mistake might mean death, hunted by roving packs of enemy vessels--but also the gnawing awareness that one of the close-knit group stands ready to betray the others. The secrecy of the mission and Ramsey's hidden purposes add to the friction. As the sub creeps toward its distant goal, the tension mounts. Special electronic detection equipment reveals the spy-broadcaster when activated, and brilliant evasive action by the captain saves the ship. But the question remains: who set it off?

The mystery of the sleeper agent's identity and the psychological problems that plague subtug crews form an intense counterpoint to the escapes that follow one after another as the sub flees enemy detection and taps the hidden well. Under Pressure is a superb war story. It is also a novel of self-discovery, of wisdom wrested from painful experience. To solve his twin mysteries, Ramsey must shed the role of psychologist and become a submariner. Only when he has confronted his own fears and prejudices, and has seen himself in the men he is supposedly analyzing, can he find the answers he needs.

The story opens with the Navy staff meeting at which it is decided that Ramsey should be sent out with the Fenian Ham. In this scene Herbert lays out the essential background and, perhaps more importantly, constructs the image of psychology that will preoccupy the characters--and the reader--throughout the book. He goes to great pains to show the power of trained psychologists over ordinary men: "Ramsey . . . allowed himself an inward chuckle at the thought of the two commodores guarding Dr. Richmond Oberhausen, director of BuPsych. Obe could reduce them to quivering jelly with ten words." "Obe," as Ramsey affectionately calls his boss, is blind; but his ability to follow the motivation and the weaknesses of others through their speech and movement patterns leaves him far from sightless. Or helpless. His control of his own behavior, his timing, and his choice of just the right words allows him to manipulate others without their knowing. It is he who is really running the meeting, not the Navy brass.

Obe wants Ramsey assigned to the mission for reasons of his own, and is close to getting his way. He needs only a convincing demonstration from Ramsey to clinch the job. At one point, when Ramsey is being shown the cylindrical device the Navy suspects is being used to give away the location of their subs, Obe interrupts:

"Mr. Ramsey's work, of course, involves electronics," said Dr. Oberhausen "He's a specialist with the instruments used for detecting traumatic memories."

Ramsey caught this cue . . . . He was the omniscient BuPsych electronics expert. The Man Who Knows Your Innermost Thoughts. Ergo: You don't have Innermost Thoughts in this man's presence. With an ostentatious gesture, Ramsey put his black box on the table. He placed the cylinder beside it, managing to convey the impression that he had plumbed the mysteries of the device and found them, somehow, inferior.

What the devil is that thing? he wondered.

"You've probably recognized that as a tight-beam broadcaster," said Belland.

Ramsey glanced at the featureless surface of the black cylinder. What would these people do if I claimed X-ray vision? he asked himself. Obe must have hypnotized them.

Ramsey is, of course, assigned to the mission. The Navy brass are hamstrung by their own fear and preconceptions about psychology, which Obe and Ramsey find easy enough to play on.

Ramsey is put through an intensive training program to ready him for subtug service. During this time, he also has an Opportunity to study the files of the other men in the crew and to try to fit them to the psychoanalytic generalizations he knows so well. The one sour note in his study is that the one man who did crack on the last voyage had easily the "best" case history of the four. The problem is far from clear cut. Obe had said, "The focal symptoms point to a kind of induced paranoia." This clue suggests to Ramsey a similarity to another problem that he had previously solved on a larger submarine, in which "the captain's emotional variations were reflected in varying degrees all through the ship's personnel."

Once Ramsey is actually on board the sub and meets the men, an important piece of the puzzle falls into place. Although they have widely different religious backgrounds, the men gather around Captain Sparrow at the beginning of the voyage:

Religious services, thought Ramsey. Here's one of the binding forces of this crew. Participation Mystique! The consecration of the warriors before the foray.

He soon sees it is more than that. The crew displays a near-religious faith in the captain's abilities. They joke about it, but there is an undercurrent of seriousness. "Skipper and God are buddies," says one of the men, his guard let down by pressure sickness. "Do favors for each other alla time." And the captain, for his part, seems to invoke this faith as a way of tying the crew together and giving them strength against the terror of the life they lead. In turn, he surrenders himself completely to divine providence. When Ramsey puts these observations together with the readings of special instruments he has monitoring the captain, which reveal icy calm during even the most extreme crises he makes a terrifying diagnosis: Captain Sparrow is a religious paranoiac, a schizophrenic destined for imminent and total breakdown!

Instinct wars with psychological analysis, however, as the pressures of the voyage drive Ramsey into the same pattern of irrational faith demonstrated by the other men. He believes he must remain "objective" to fulfill his role as a psychologist, but he cannot easily maintain this stance. The first time the submarine goes down close to its depth limit in an effort to escape pursuit, he finds himself reacting unexpectedly:

What is Sparrow's reaction to the increased danger? he wondered. Then: I don't really care as long as his ability keeps me safe.

The thought shocked Ramsey. He suddenly looked around his electronics shack as though seeing it for the first time, as though he had just awakened.

What kind of psychologist am I? What have I been doing? As though answering a question from outside himself, his mind said: You've been hiding from your own fears. You've been striving to become an efficient cog in this crew because that way lies a measure of physical safety.

As he wakes up to this realization, fear smashes him. He freezes. And it is Sparrow himself who notices and comes to Ramsey's rescue, giving him the fathering he desperately needs to get through the terror. "I've been waiting for this, Ramsey," he says. "Every man goes through it down here. Once you've been through it, you're all right." This is Ramsey's initiation into the strange world where these deep submariners have learned to survive.

His own experience now tells Ramsey that the pseudoreligious mystique of the crew plays a crucial role in its success; but his psychological training convinces him that it will also be the fatal flaw, the source of the psychotic break he was sent to stop. He decides that he must do something to shatter the pattern. He begins to antagonize the captain at crucial moments. If he can only get him to fail at just the right moment, yet without endangering all their lives, the spell will be broken.

What Ramsey does not consider is that in the tight-knit community of the sub he cannot upset the captain without upsetting the entire crew. And it is not Sparrow who breaks first. Les, another of the crew, concludes that Ramsey is a spy after he finds him at work alone in the electronics shack when he should be off duty. He attacks Ramsey unexpectedly. Actually, Ramsey has just discovered the trigger mechanism for the enemy tight-beam broadcaster, and when he awakens from unconsciousness surrounded by the captain and the other men, his first thought is to warn them lest they accidentally trigger it again. Les is abashed, and later apologizes to Ramsey

This incident, along with a number of others, leads the crew to suspect Ramsey's real role on board. Despite their resentment, they begin to confide in him. Les tells Ramsey:

"What I'm trying to say is that I've felt better ever since I pounded you. Call it a cathartic. For a minute I had the enemy in my hands. He was an insect I could crush."

"So?"

"So I've never had the enemy in my hands before." He held up his hands and looked at them. "Right there I learned something ... When you meet your enemy and recognize him and touch him, you find out that he's like yourself: that maybe he's part of you.. . . It's like when you're the youngest and weakest kid on the playground. And when the biggest kid smacks you, that's alright because he noticed you. That means you're alive. It's better than when they ignore you. He looked up at Ramsey. "Or it's like when you're with a woman and she looks at you and her eyes say you're a man. Yeah, that's it. When you're really alive other people know it."

"What's that have to do with having the enemy in your hands?"

"He's alive," said Bonnett. "Dammit all, man, he's alive and he's got the same kind of aliveness that you have."

The scene is interrupted by enemy pursuit, but what Les said comes back to Ramsey later, when he finally uncovers the identity of the enemy agent on board. The man has been coerced into betrayal by a threat to his wife and children, but underlying this motivation is a basic malaise brought on by the never-ending war. A part of him assents to the betrayal, "just so somebody wins and that puts a stop to the thing--the bloody, foolish, never-ending thing." Ramsey begins to see a new dimension to his problem. It is not the men who are unbalanced, but the situation. The madness of war and secrecy breaks down that awareness and communication of aliveness between individuals that Les was talking about. Sparrow, whose "religious mania" leads him to pray for the men he kills, starts to look like he has the only "scratch of sanity" in the whole situation.

If Herbert had left the solution at this point, as a criticism of the insanity of war, the novel would display merely commonplace insight. But this is only the first stage of the solution. Sparrow himself, not Ramsey, uncovers the rest. When Ramsey finally confronts him, Sparrow is unperturbed. He admits to the symptoms Ramsey has isolated in his case--the icy calm in which normal fear responses are suppressed by the mind, the machinelike identification with the submarine as though it were an extension of his own body, the overriding religious faith--but he contests the conclusions:

"Here in the subtugs, we have adapted to about as great a mental pressure as human beings can take and still remain operative. We have adapted. Some to a greater degree than others. Some one way and some another. But whatever the method of adaptation, there's this fact about it which remains always the same: viewed in the light of people who exist under lesser pressures, our adaptation is not sane . . . ."

"I'm nuts," said Sparrow. "But I'm nuts in a way which fits me perfectly to my world."

Sanity is not a state of mind, it is a relationship between individual and environment. Sparrow goes on to say that we imagine Utopia, the perfect society, as a place completely without pressures of any kind; and our idea of sanity is deeply colored by that view. We forget that none of us has ever lived in that kind of utopia, and never will. Sanity must always be a compromise, a relativism. Ramsey's own adaptation, Sparrow points out, is a product of his psychological training. "You have to believe that I'm insane, and that your diagnosis of insanity type is accurate. That way, you're on top; you're in control. It's your way to survival." Heppner, the previous electronics officer, cracked up when he began to question the sanity of his adaptation and tried to force himself back into the mold of "surface" thinking, rather than undersea thinking.

All through this conversation with Sparrow, Ramsey has been feeling a mounting excitement, "as though he were on the brink of a great realization." He is both excited and afraid of what he is about to see. As Sparrow has pointed out, it will challenge his own adaptation. So when the captain makes his final point, Ramsey passes out, a last-ditch attempt to avoid a new and threatening understanding. When he comes to, after hours locked in a fetal ball, he has all the pieces of the puzzle. Sparrow's last insight and his own reaction were the final clues. What Sparrow had said was this:

Ramsey could contain the question no longer. "What's your definition of sanity, Skipper?"

"The ability to swim, said Sparrow That means the sane person has to understand currents, has to know what's required in different waters."

Sanity is not just the result of adaptation to a given situation, but the ability to adapt. At its best, this requires a heightened awareness of self and environment. Sparrow has this self-awareness in great degree. Other men are less fortunate. They are unable to shift back and forth between the different "sanities" (or insanities) of the undersea world and the surface. This is the real source of the breakdowns in the subtug crews. The men are caught in a double bind. Because of the special adaptations they have made, life in the subs, for all its danger, feels more secure and uncomplicated than life outside. In addition, there are subconscious psychological factors at work, as Ramsey realizes from his own retreat into catatonia: the subconscious perceives the submarine as a kind of womb, the underwater tunnels through which the vessel returns to its hidden base as a kind of birth canal, and the return to the surface as birth into an unknown and hostile world. "The breakdowns are a rejection of birth by men who have unconsciously retreated into the world of prebirth," he concludes.

Ramsey's solution is to try to "make the complete cycle desirable," or, at the very least, to reduce the split between the two sides of the submariner's life. One important step that must be taken is to rid the corps of antiquated security restrictions. "'We'd be better off without Security,' muttered Ramsey. 'We should be working to get rid of it. Security stif1es communication. It's creating social schizophrenia.'" The enemy already knows the location of the secret submarine bases; they know the subtugs are pirating oil from their waters. Secrecy about these matters keeps nothing from them, but it does keep the two sides of each submariner's life rigidly apart. A version of "the old Napoleonic fancy uniform therapy: fanfare coming and going" would do wonders for the morale--and sanity- -of the subtug crews.

With this realization, Ramsey's quest is over. The homecoming of the sub with its cargo of oil is anticlimactic. The solution of the puzzle has been bewilderingly complex, each answer giving way to another, each with a weight of concepts that would have overwhelmed any but the most tightly written novel. It all works in Under Pressure because the conceptual unfolding is matched step by step in the action of the plot. The ideas never interrupt the action; they are tightly woven into it. This success at blending ideas and storytelling is a direct result of the nature of Herbert's psychological insight, as pointed out by Ralph Slattery: it is based on character, not on concepts. And so it is not as though there are two levels operating in the novel--the level of action and the level of thought--but as though thought in every case springs from what happens. This is careful realism. Ramsey's involvement in what is going on provides the material--and the matrix-- for his thought. Herbert never defaults into the lazy trap of omniscience. Every detail that is brought to the attention of the reader is noted by someone, or involves him in action. On the rare occasion when Herbert does make an "omniscient" comment, he swiftly reinvests the new concept in the action of the story. For instance:

There had been a time when people thought it would solve most seafaring problems to take ocean shipping beneath the surface storms. But, as had happened so many times in the past, for every problem solved a new one was added.

Beneath the ocean surface flow great salt rivers, their currents not held to a horizontal plane by confining banks. The 600 feet of plastic barge trailing behind the Ram twisted, dragged and skidded....

The ongoing dialectic of problems and solutions is one of Herbert's favored observations; he cannot resist making it. But it adds to the drama. The sub is caught in a conceptual current!

The unity of action, character, and concept in Under Pressure shows the heritage of Ralph Slattery, the idea that psychology is about people, not theories. But the key to Herbert's ability actually to transform psychology into dramatic technique is the interest in nonverbal communication that he shared with Irene. We have already seen how "Obe" used his awareness of nonverbal cues to manipulate the Navy brass. Ramsey, too, notes appearance and gestures as well as words and actions. "That mannerism of rubbing his neck, thought Ramsey. Extreme nervous tension well concealed. But it shows in the tight movements." And so on. Herbert is always aware that thought and emotion are embodied. The story is set up perfectly to give full play to this viewpoint. Ramsey is deeply involved in the action, but he must also observe and study the other men. So the reader sees multiple layers of viewpoint at once: the action itself (in the tiny subtug, the action of one man involves all), the introspective reaction of Ramsey and sometimes Sparrow, the behavioral response of each character and Ramsey's conclusions about it. The effect is somewhat similar to the play-by-play reporting of a sports announcer.

This many-layered effect could have slowed down the pace; rather, the pace is hastened, because until the end Herbert is content to hint, and does not always elaborate on each level. Ramsey may note some clue but be unable to draw a conclusion from it. His reflections end in mystery. And so the reader becomes involved with him, not in his analysis, but in heightened perception of the characters. No more than Ramsey does he have the facts that will confirm the identity of the sleeper agent or predict a crackup. The reader becomes engaged in Ramsey's struggle to understand the myriad, seemingly unrelated, factors. Furthermore, not every thought is completed. Just when Ramsey feels himself to be on the brink of realization, a new crisis will occur that thrusts him rudely back to the more urgent task of survival. The net result is that the reader is never allowed entirely to desert the realm of involved action for the realm of thought. He is always brought to the brink, and then stopped. The continual tension between thought and action yields a powerful illusion of life, and from life one does not expect the simple answers you sometimes find in stories. When in the end the answers pour out in a rush, their weight and complexity are easily overbalanced by relief at finding a solution at all.